Zagreb - Gornji Gardec

| Like Kaptol, the history of Gornji Gradec is interwoven with the history of Zagreb and its Old Town. I have included a detailed history for the entire city on an associated page. |

Going from Kaptol into Gornji Gradec, I passed

through the Kamenita vrata, or the stone gate. This gate

was the original passage point between the two towns. The gate is hidden

in an alcove; the only reason that I found it was because I followed a

crowd. Without a crowd guiding you, the best way to find it to look for

the statue of Saint George slaying the dragons. This statue is located

about half way up Radićeva ulica on the western side of the

street. The alleyway will switches back to the south, at the end of which

I found the alcove.

Going from Kaptol into Gornji Gradec, I passed

through the Kamenita vrata, or the stone gate. This gate

was the original passage point between the two towns. The gate is hidden

in an alcove; the only reason that I found it was because I followed a

crowd. Without a crowd guiding you, the best way to find it to look for

the statue of Saint George slaying the dragons. This statue is located

about half way up Radićeva ulica on the western side of the

street. The alleyway will switches back to the south, at the end of which

I found the alcove.

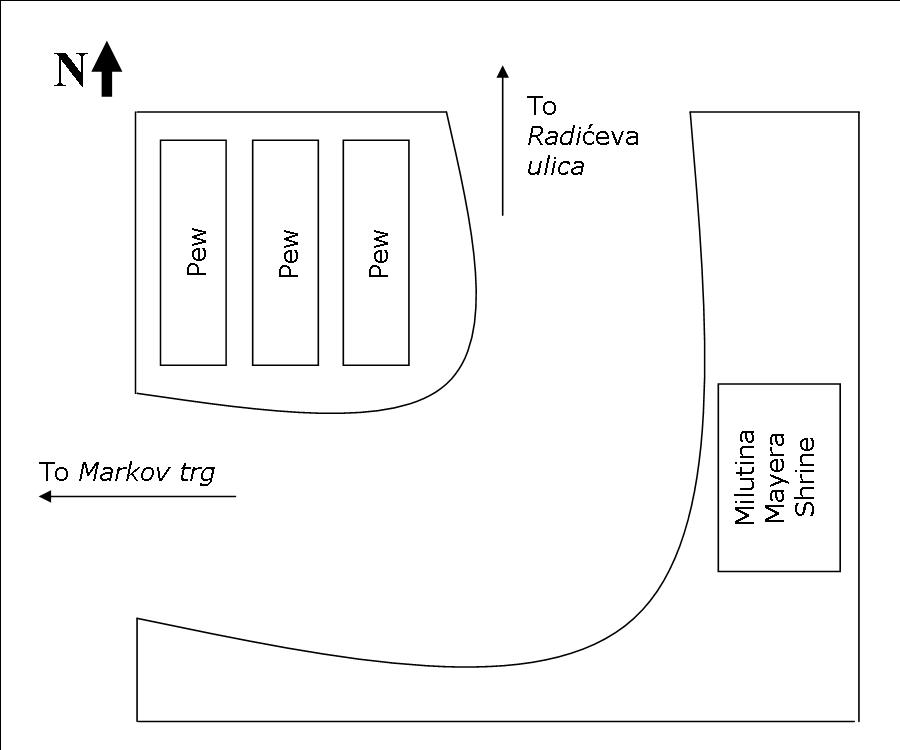

As I entered the alcove, I quickly realized that it was the shrine to the Virgin Mary, known located as the Milutina Mayera. According to legend, a fire in 1731 destroyed every wooden component of the original gate except for the painting of the Virgin Mary and Child. The local people believe the surviving painting possesses magical powers - they come to pray before it and leave flowers. The actual door, or what I assumed to be the door, was contained behind glass and heavy metal mesh. There were tribute candles burning at the base and a few people praying in the pews facing the shrine. There were a few people kneeling at the shrine. Almost everyone that entered the alcove stopped, crossed him/herself, said a prayer and proceeded. It was truly an amazing spectacle - a testament to the deep Catholicism that this country has.

Heading south from the gate, I came to the Galerija Klovićevi Dvori. Housed in a former Jesuit monastery, it is the pre-eminent location for the display of modern Croatian art. There are two reasons that I did not visit the museum: first, I am not a big fan of modern art; and secondly, the museum appears to be under renovation. The exhibition posters indicated that it was open, but I could no discern where the entrance was located. Had I visited the museum, however, I could have seen the works of Mila Kumbatović.

Next

to the gallery is the Crkva Svete Katerine, the Jesuit church dedicated

to Saint Catherine. Built between 1620 and 1632, this Baroque-styled

church contains a beautiful interior of pink stucco and white lacework.

Frescoes on the ceiling depict the life of saint after which the church is

named. The building was open so I decided to enter. There was a

choir practicing in the upper balcony, which made for a nice musical environment

in which to view the church. The main altar, dating from 1762, was

exquisite, especially the paintings behind it. There are six other altars,

which are, in clockwise order from the northwest corner: Kapela Svete

Apolonije, Kapela Duhe Svetoga, Kapela Svetog Ignacija Lojolskoga,

Kapela Svetog Franje Borgija, Kapela Svetog Dionizija and Kapela

Svete Barbare. The altar honoring Saint Ignacious Loyola contains a

statue of the saint by Robba.

|

|

| Crkva Svete Katerine, the Jesuit church honoring Saint Catherine |

Just

west of the church is the Kula Lotrščak, which is shown in the

picture below. Fearing another Tartar invasion in the 13th c.

CE, the citizens of Gradec asked King Bela IV in 1247 to construct a safe hiding

place. He obliged and fortified the city between 1247 and 1266; this tower

is one of the oldest and best preserved remnants of this effort. The tower

received its name from Campana Latrunculorum, or the tower of

thieves. The tower's bells would be rung every night before the town's

gates were closed; this would be an indication to thieves that

Just

west of the church is the Kula Lotrščak, which is shown in the

picture below. Fearing another Tartar invasion in the 13th c.

CE, the citizens of Gradec asked King Bela IV in 1247 to construct a safe hiding

place. He obliged and fortified the city between 1247 and 1266; this tower

is one of the oldest and best preserved remnants of this effort. The tower

received its name from Campana Latrunculorum, or the tower of

thieves. The tower's bells would be rung every night before the town's

gates were closed; this would be an indication to thieves that

they should in town to get their evening's work done. The top two floors

were added in the 19th c. CE, at which time the tower was used to survey the

town for fires. Once I reached the observation platform, I could

understand this use; there are magnificent views of the city. It was also used

as a wine cellar, before being acquired by the city and restored.

Every day at noon, the tower's cannon is fired. Legend states that this tradition began during the Turkish occupation in the 15th c. CE. The cannon was fired at the invading forces, but instead of hitting one of the Turkish legions, it struck a rooster. The cannonball destroyed the rooster, which scared the Turks into retreat. A more common explanation is that the cannon was fired so that the churches could synchronize their clocks. The view from the top is worth the HRK 10 entrance fee alone. The ticket box is about half way up the tower, at which point visitors can view the cannon that is fired every day.

I

headed north from the tower on Ćirilometodska ulica. About a

block north, on the west side of the street, is the Hvratski

muzej naivne umjetnosti, the country's museum of naďve art.

Croatia has a long history of folk art, and this museum celebrates their

talents. Enter the museum through the alleyway; the door is on the right

hand side. This museum is located on the sixth floor and has six rooms

that display some of the 1500 pieces in the collection. Most of the

paintings were done on glass, as opposed to canvas, which I found to be an

interesting fact. Some of the highlights included Franjo Mraz's Brigada

(The Brigade, 1956); Mijo Kovačić's Raspelo, which dominated

the second room; and Emerik Feješ's paintings of cathedrals in a number of

European cities (Paris, Venice and Vienna). I highly recommend a visit to

the museum and the bookshop, which has an excellent collection of exhibit

posters for sale.

I

headed north from the tower on Ćirilometodska ulica. About a

block north, on the west side of the street, is the Hvratski

muzej naivne umjetnosti, the country's museum of naďve art.

Croatia has a long history of folk art, and this museum celebrates their

talents. Enter the museum through the alleyway; the door is on the right

hand side. This museum is located on the sixth floor and has six rooms

that display some of the 1500 pieces in the collection. Most of the

paintings were done on glass, as opposed to canvas, which I found to be an

interesting fact. Some of the highlights included Franjo Mraz's Brigada

(The Brigade, 1956); Mijo Kovačić's Raspelo, which dominated

the second room; and Emerik Feješ's paintings of cathedrals in a number of

European cities (Paris, Venice and Vienna). I highly recommend a visit to

the museum and the bookshop, which has an excellent collection of exhibit

posters for sale.

Ćirilometodska

ulica ends at Markov trg, the square on which three of the most

important buildings in Croatian history sit. On the east side is the Sabor,

which is the country's parliament. Constructed in 1910 in the neoclassical

style, the building replaced a series of townhomes from the 17th and

18th c. CE. It was from the center balcony that Croatian

independence was declared in 1918.

|

|

| The front of the Sabor, which is home to the Croatian parliament |

To the north of the square is the Crkva svetog Markva, a church honoring Saint Mark. The original church on the site was constructed in the 13th c. CE and named for the Saint Mark's fair, which was held annually in Gradec. The current church was constructed in 1880 with the distinctive roof that displays the medieval coats-of-arms for Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia on the south side and the the city's emblem on the north side (I believe these emblems are on the bell tower, and not the roof). The present bell tower replaced an earlier one that was destroyed in the 1502 earthquake. I could not find the entrance to the church, and did not linger too long to investigate further. Because of all of the government buildings around the square, there were a number of police officers roaming around the area. I didn't want to draw any suspicion to me, so I went along my merry way.

|

|

|

|

The southern roof of Crkva svetog Marka, as seen from the Kula Lotrščak. Notice the emblems of the Croatian regions. |

The northern roof, which had a beautiful checkered pattern of blues and reds. |

|

|

|

| The present tower, which replaced the one destroyed in the 1502 earthquake. The upper windows appear to have emblems underneath them, which are those of the provinces and the city. | This is the main portal, which is located on the west side of the church. It was carved in the 14th c. CE and contains sculptures of fifteen figures in shallow niches. |

On the west side of the square is the Banski Dvori, which now houses the Croatian president. The two Baroque mansions once houses the country's bans, which were the viceroys that ruled in the Middle Ages. In 1991, during the war of independence, the building was bombed by the Yugoslav federal army in an assassination attempt against then-president Franjo Tuđman. The square in front of the palace has been used to inaugurate Croatian leaders since the 16th c CE; most recently in 1999 when Stjepan Mesić succeeded the ailing Tuđman.

|

|

| The Banski dvori and the courtyard that has witnessed the inaugurations of Croatian rulers since the 16th c CE. |

North of the Markov trg on Opatička ulica is the Muzej

grada Zagreba, which chronicles the city's history in artifacts and

photographs. The museum is housed in the former convent of the the Poor

Saint Claire's order, known locally as the Samostana optica Klarisa.

In 1212, Saint Claire of Assisi founded this Franciscan order. In 1646, a

number of nuns came to Zagreb to establish a presence in Croatia. By June

1650, the convent had been completed and a number of Croatian nuns, mainly from

the country's aristocratic families, enrolled in the order. In February

1782, Emperor Joseph II decreed the end of religious orders like Poor Saint

Claire's.

|

|

| The exterior of the former Samostana optica Klarisa, which now houses the city's history museum |

The Rough Guide calls the museum "... the city's best ..." and I would have to agree with that assessment. Through an uninspired entry way, the visitor enters the museum through an exhibit that presents the recent archaeological work that has occurred on the site - including three wooden buildings from the medieval period and a workshop from the late Bronze Age or early Iron Age. From the exhibit, the visitor travels from room to room, which display the history of the town through artifacts, paintings, pictures and photographs. Most of the captions are written in Croatian only, but there are storyboards that are written in English. It is from these storyboards that I was able to write the history of Zagreb. I highly recommend spending the HRK 20 to enter the museum.

The

historical architectural feel has been maintained in the area around the

museum. In spite of the cars parked along both sides of the street, there

was a real medieval ambience to the neighborhood. I was able to peer into

some of the courtyards - some of which I'm sure housed horses and chickens in

earlier times.

| The neighborhood's medieval roots can been seen in the architectural of its houses | A courtyard between some houses. How many horses have been stabled here? |

There

are two additional museums in Gradec, neither of which I visited. The Hrvatski

povijesni muzej displays exhibits on the nation's history, while the Hrvatski

prirodoslovni muzej is the country's natural history museum. I

could not find the former museum, and the latter's subject matter did not

interest me. So I meandered back to the Kula Lotrščak, which is near

one of the termini for the Uspinjača. Costing HRK 3 for a

one-way ride, this funicular transports passengers between the Upper and Lower

Towns. It was built in 1890 and electrified in 1934. The 66-meter

trek traveled at a 27° angle or 51% grade. It departs every ten minutes and takes about five minutes to

complete - a rather pleasurable experience.

There

are two additional museums in Gradec, neither of which I visited. The Hrvatski

povijesni muzej displays exhibits on the nation's history, while the Hrvatski

prirodoslovni muzej is the country's natural history museum. I

could not find the former museum, and the latter's subject matter did not

interest me. So I meandered back to the Kula Lotrščak, which is near

one of the termini for the Uspinjača. Costing HRK 3 for a

one-way ride, this funicular transports passengers between the Upper and Lower

Towns. It was built in 1890 and electrified in 1934. The 66-meter

trek traveled at a 27° angle or 51% grade. It departs every ten minutes and takes about five minutes to

complete - a rather pleasurable experience.

Proceed to the Donji Grad

or return to the Zagreb Main Page