Day 3 - Retiro and San Nicolás

It started as another beautiful day in Buenos Aires. Unfortunately, I did not start as early as I would have liked, but the extra sleep certainly helped me. I had breakfast at the hotel, and, though it was complimentary, it wasn't very good. After quickly reading through my travel guide, I began my adventure through two barrios - Retiro and San Nicolás.

Retiro

According to the Lonely Planet guide,

"... the barrio of Retiro derives its name from its former status as

a monks' retreat on the city's outskirts during early colonial times"

(88). The barrio now provides the buffer between the bustling

downtown area and the more sedate residential barrios to the north. It

houses the city's largest railroad station, as well as its finest hotels and

shopping outlets.

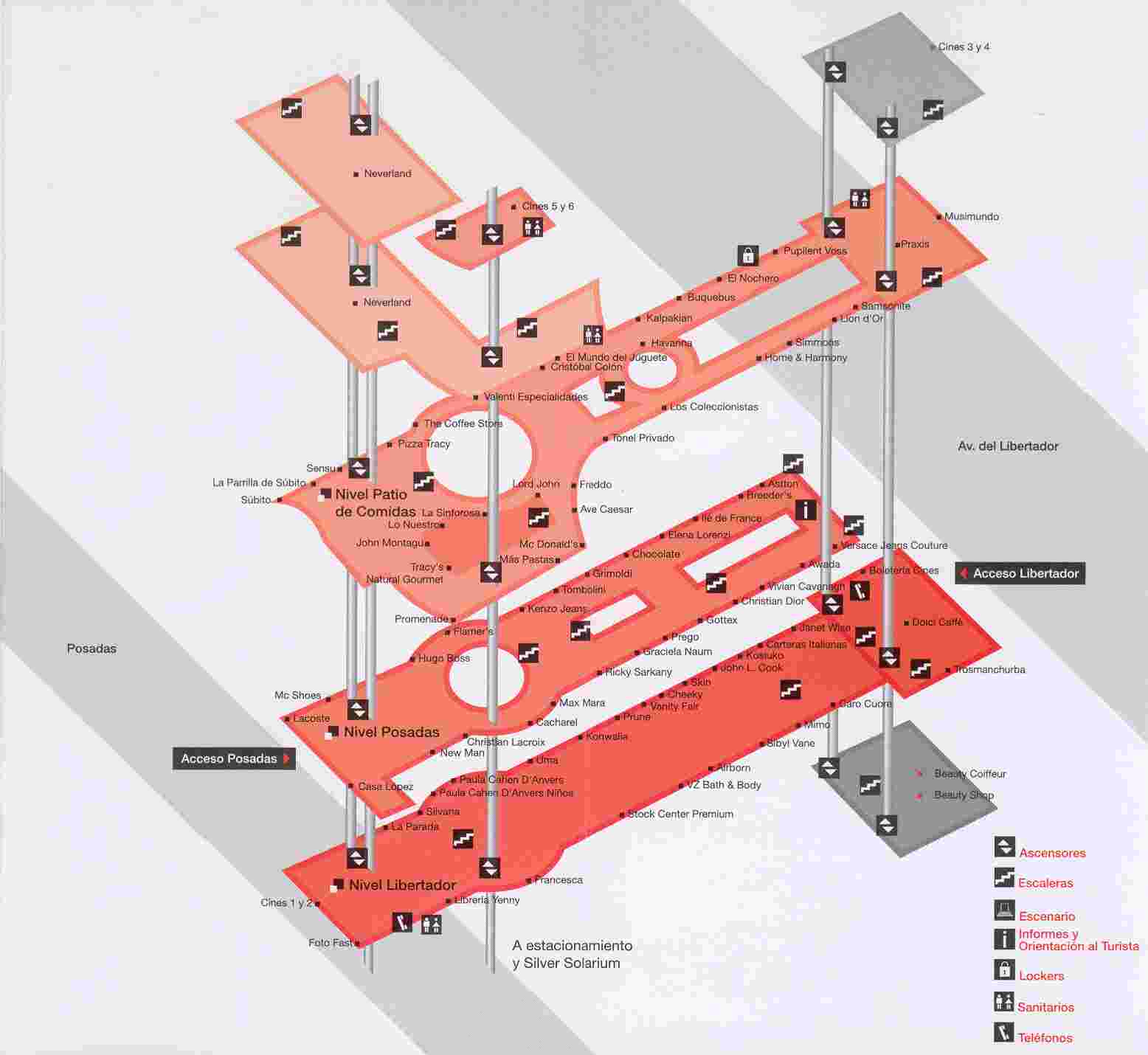

The day's tour started near the Patio Bullrich shopping mall. As well as being the oldest mall in the city, it is the most luxurious. The building originally served as the city's meat auction house, but, in 1988, it was transformed into a mall that caters to the city's more affluent citizens. High-end women's fashion is sold at Christian Lacroix, Max Mara and Versace, while men's fashion can be found at Christian Dior and Hugo Boss. Located on the third floor of the mall is El Nochero, which sells leather and suede coats, as well as silver jewelry and expensive mates. I wasn't that impressed with the store's selection or its prices - better deals can be found throughout the city.

Located on Calle Posadas, which runs behind the shopping mall, are some of the city's most exclusive hotels, including the Caesar Park Hotel and the Four Seasons Hotel. Both hotels were far out of my price league - I'd rather spend my money on souvenirs and not expensive hotel rooms. In front of the Four Seasons Hotel was the beautiful Plazoleta Isidero Ruiz Moreno, which had blooming purple flowers and black sculptures of zoo animals.

Across the street from this park was the Galería Zurbarán, which represents some of the country's top artists. It was displaying works by Argentine artist Raul Soldi, who was being shown at an Zurbarán-sponsored exposition at the Palais de Glace (Day 4).

Down the street from the gallery is the Plaza Pellegrini. The beautiful square has a statue of the former Argentine president and founder of the Jockey Club, a Angophile society whose headquarters now faces the square. In front of the statue is a fountain that is surrounded by beautifully-trimmed hedges. Also located on the square are the embassies of Brazil and France, which refused to move during the expansion of the Avenida 9 de Julio.

The Jockey Club was created for wealthy racehorse owners and those who bred polo horses. This is the organization's third location: the first was demolished when the Avenida 9 de Julio was widened in 1931 and the second was burned during the Perónist revolts of 1955. This male-only club allows women in the dining room only and requires men to wear jackets.

Heading south on Avenida Libertad is the Plaza Libertad. In the center of the square is a statue of Adolfo Alsina, a former minister of war and marine activities (navy). The square is also home to a large gomero tree, which provides shade on the city's hot summer days; a picture of this tree is shown below. It was lunchtime when I passed through the plaza - there were numerous sunbathers and others eating their mid-day snack.

A block south of the plaza is the Teatro Nacional Cervantes, which is the capital's old lyric opera theatre. Named for the Spanish author of Don Quixote, the theater's façade is a replica of the Universidad de Acalá de Henares in Spain. The idea for the theater originated with Spanish actress María Guerrero and it opened in 1921. The theater now hosts a number of events, as well as a small museum in the front arcade. The basement contains an archives section that focuses on Latin American theater.

San Nicolás

Also known as Microcenter,

the barrio of San Nicolás is the business and commercial center of the

city, as well as the center of government for the Argentine republic. The

first place visited in the barrio was the Plaza Lavalle. Originally

named the Plaza de Armas for the small munitions factory that had been located

here previously, the plaza received its current name when the monument was

raised to honor one of the military heroes that crossed the Andes with General

San Martín. The plaza covers three blocks and appears to be a center of

activity for the barrio. In addition to the plethora of dogwalkers

and sunbathers, there are a number of secondhand book stalls located at the

south end of the plaza.

On the east side of the plaza is the Teatro Colón, one of the city's truly magnificent architectural gems. Named for Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, the current theater was constructed in 1908 and opened with Verdi's Aida. Its main theater has seating for almost 2500 people, plus standing room for an additional 1000 patrons. The dome in the main lobby contains a mural by Argentine painter Raúl Soldi. There is a small Museo del Teatro Colón that displays many objects related to the theater; unfortunately, I did not have time to visit.

Across the square from the theater is the Palacio de Justicia, better known as the Tribunales. Designed by French architect Norbert Maillart, this austere building reeks of the slow, arduous legal process that exists in this country. It is so ugly that I won't even show a picture of it.

Located at the corner of Montevideo and Sarmiento is Chiquilín, a classic parrilla, or Argentine steakhouse. I ate dinner at this restaurant and had a wonderful meal. It started with a salad that consisted of lettuce, corn, beets, green beans, kidney beans, carrots and tomatoes; the salad was topped with a wonderful oil-and-vinegar salad dressing. The main course was a steak called the Bife Chiquilín, which wasn't the best cut of meat, but good nonetheless. It came with a fried egg and strip of bacon on top, a very Latin American presentation. Including my large bottle of Argentine red wine, which I did not finish, the dinner cost $14.28 (ARS 50).

Heading south from the restaurant's location is the Pasaje de la Piedad. The passageway is a residential block that has been made famous through television and movie location-shooting. It is a beautiful and tranquil setting, and it appeared that some of the residences were being renovated. The block is named for the parish church across the street, Nuestra Señora de la Piedad del mon Calvano.

East of the passageway is the Avenida 9 de Julio, which the proud Argentines claim is the world's widest avenue. At 460 feet and twenty traffic lanes wide, the street took its current form in the 1930s. I was surprised that the traffic flow wasn't as excessive as I had expected. At the intersection of the avenue and Avenida Corrientes is the Plaza de la República and its Obelisco. Designed by Alberto Prebisch, the obelisk commemorates the 400th anniversary of the founding of Buenos Aires. Since its installation in 1936, the structure has been the subject of various jokes, which mainly refer to its phallic nature. In 1939, the city council voted 23-to-3 to demolish the monument, but it has endured through time. On each of the obelisk's four sides are scenes important to the city's founding, including Mendoza's foundation in 1536, Garay's refounding in 1580 and the establishment of the city's national capitol status in 1882. On the north side of the plaza are 24 placards representing each of the country's provinces - buried under each placard is soil from the province.

Heading east on Avenida Rivadavia in the direction of the river, I came upon the Plaza de Mayo. I wasn't scheduled to visit the square until Day 6, but the buildings on the north side of the plaza were on this day's activities. On the northwest corner of the square is Catedral Metropolitana, the seat of the Archbishop of Buenos Aires. The present church, the fifth one to stand on this site, was consecrated in 1836. The cathedral's plan was devised in 1743, the first façade was blessed in 1791 and the final touches were completed in 1910. Since most of the construction occurred in the early 19th century, it is considered one of the finest examples of neoclassicalism architecture in the city. The interior is decorated beautifully, and it appears to have been restored recently.

On the east side of the cathedral is the mausoleum that houses the remains of General José San Martín, famous for crossing the Andes and liberating deep South America from Spanish rule. The entrance to the mausoleum is guarded by two members of the military, dressed in traditional uniforms. His coffin stands a four-meter high base and is draped with an Argentine flag. On the front of the church is an eternal flame remembering General San Martín.

|

|

|

Further east on the square is the Banco de la Nación building. Built in 1888, the building is home to the nation's central bank. The public is prohibited from entering the main building, rather they are directed to the Museo Histórico y Numismático del Banco de la Nación Argentina. Unfortunately, the museum was closed when I visited the area. Northeast of the cathedral is the Banco de Boston building. Built in 1924, the building's entranceway was carved to the United States and shipped to Argentina for installation. The doorway can be seen in the picture below. The building is covered in graffiti, an obvious target of the country's aggression in this financially troubling time. One slogan said referred to Americans as "bastards".

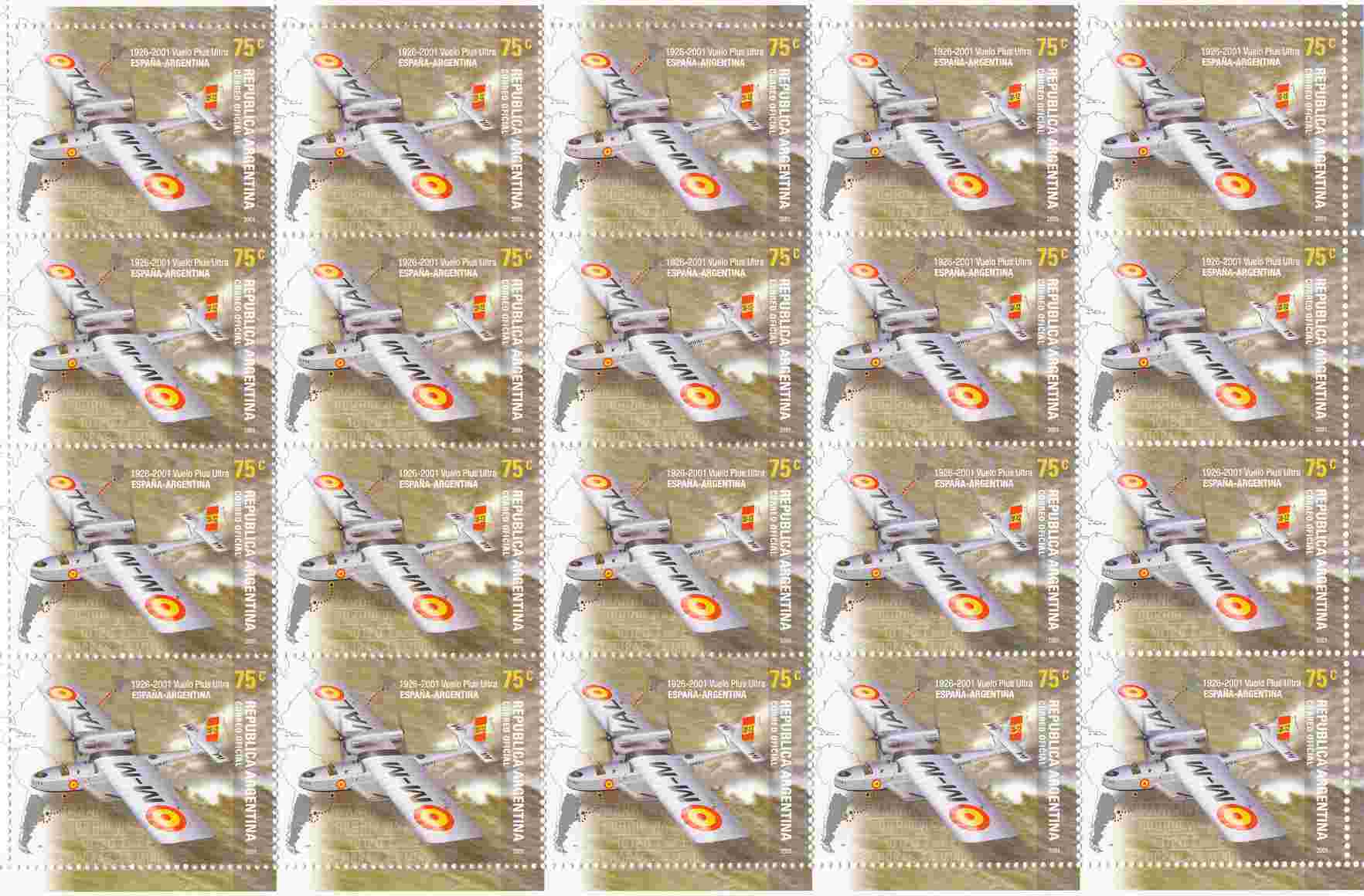

North-northeast of the Plaza de Mayo is the Correo Central, home of the Correo Argentino national postal service. Designed in the Beaux Arts style by Norbert Maillart, the post office is modeled after the similar purpose structure in New York City. It was completed in 1928, with the two-tier mansard roof added later. The philatelic division is located on the first floor on the west side of the entry hall. I purchased some sheets of stamps to add to my selection, including the sheet below that commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Buenos Aires-to-Madrid air route.

Heading east from the post office, I reached Avenida Florida, which is the city's main pedestrianized shopping street. Located here are a number of clothing, sporting goods and jewelry stores. In spite of the horrible economic situation, there appeared to be many people shopping - judging by the number of pedestrians with shopping bags. On the street was the only Harrod's outlet outside of London. It closed in 1997 due to declining sales.

At the northern end is the Galerías Pacíficos shopping mall. The building was built originally to house an outlet of the French Bon Marché department store. An economic crisis forced the French group to abandon construction with only one wing completed. The building served several interim purposes before it was purchased by the Railway of the Pacific and renamed Edificio del Pacífico. In 1945, the railway company decided to install a shopping arcade in the lower level of the ground floor. At the same time, a mural was added to one of the domed ceilings; five Argentine artists were commissioned to paint the mural. Between 1961 and 1989, the building stood vacant, until is was reopened in 1992 as the Galerías Pacíficos shopping center. I took a break from my tour to enjoy some people watching and a cold Diet Coke at one of the mall's cafés. While I would have enjoyed sitting outside, the temperature was approaching almost 30°C outside.

Retiro - Again

From the Galerías Pacíficos, I

headed back into Retiro to finish the day's tour. Unforuntately, I did not

visit the three famous plazas in this barrio - Plaza Libertador

General San Martín, Plaza Fuerza Aerea Argentina and Plaza Canada.

It'll give me something to do on my next trip to Argentina.

One of my many great shopping experiences in Buenos Aires was at Wayra, a store on Avenida Santa Fe that specializes in indigenous crafts from the northwestern provinces of Salta, Catamarca and Jujuy. I bought four pieces of pottery from this store (one, unfortunately, broke during the trip home). If you're interested in pottery, I highly recommend a visit to the store.

After these stops, I headed back to the hotel. As I mentioned above, I had dinner at the Chiquilín restuarant. I spent the latter part of the evening sitting at an outdoor table of the Babieca café on Avenida Santa Fe. In between sipping my hot tea and eating a piece of fruit pie, I contemplated the meaning of life and tried to find answers to many of its questions. I did come to some conclusions, which has provided me with some direction.

Click here to proceed to Day 4 - Belgrano, Palermo and Recoleta or return to the Argentina main page.

Background Information

Carlos Pellegrini was a protégé to the Julio

Roca, who was the first president in Argentina’s enlightened era.

Pellegrini became a prominent member of the Argentine political scene in

the 1870s. There had been much

discussion on how to strengthen the nation’s industries, such that they could

compete with the economic powerhouses of Germany, the United Kingdom and the

United States. A group that was led by Pellegrini favored protection of

infant industries for those “… goods for which raw materials were

potentially cheap and abundant, mostly agricultural or pastoral goods. Efficiency and the protection of consumers against

exploitation domestic monopolies, he maintained, made it desirable to continue

importing most manufactured goods; diversification should proceed only within

the prevailing agrarian framework” (Rock, 150).

Consequently, the only industries that received protection under this

framework were those that produced flour, sugar and wine.