Split

My description of Split is separated into several sections. Links to each section are provided below:

Introduction

Split

sits on the Croatian Adriatic coast, in a region known as Dalmatia. The

oldest part of the city sits nestled around a natural harbor and a wooden, hilly

peninsula extends in a southwest direction. It is the country's second

largest city, with a population of roughly 220,000 people.

Split

sits on the Croatian Adriatic coast, in a region known as Dalmatia. The

oldest part of the city sits nestled around a natural harbor and a wooden, hilly

peninsula extends in a southwest direction. It is the country's second

largest city, with a population of roughly 220,000 people.

History of

Split

In the 4th c. CE, Dionysius I, ruler of the Sicilian city of Syracuse,

established a colony on the island of Vis, which is one of the most remote

Croatian islands from land. Located about 60 kilometers south-southwest

from Split's current location, the colony was called Issa initially. To

facilitate trade with shore-bound Illyrian tribes, the colony established

outposts at Tragurion, Salona and Epetion. These outposts later would

become Trogir, Solin and Stobreč, respectively.

During the Roman conquest of the first century BCE, Salona became the capital of the Upper Illyricum province, which later would become Dalmatia. A small fishing village formed at the coast; it was named Aspalathos. Its earliest inhabitant was mentioned in 48 BCE - Arhebije, son of Kleodik and Filiks, who was the son of Drop. This settlement is not mentioned in the early records; historians hypothesize that either it formed later than its neighbors or it was not important.

Born in the capital city, Emperor Diocletian built his magnificent palace (link) on the coast near this fishing village. When he died, his palace became state property. For the next three centuries, the palace would entertain rules and Roman officials until it fell into a state of disrepair in 6th c. CE. In 614, the invading Avars and Slavs struck Salona, forcing its residents to flee to the Adriatic islands. Once the threat subsided, the refugees returned to the mainland about six years later and converted the dilapidated palace into a commune. This settlement was known as Spalatum or Spalato.

In 678, the city succumbed to Byzantine rule under Emperor Constantine II Pogonatus. Split did maintain, however, a certain degree of autonomy. By the 9th c. CE, it had developed trade relations with the inland Croatian state, serving as the latter's access to the Adriatic Sea and lucrative Mediterranean trade routes. It was during this period that Byzantium granted Venice the right of control through proxy. It was until Krešimir IV took the throne in 1058 that Croatia (Dalmatia and the interior) were unified under the same ruler.

As an archbishopric, Split hosted two church councils, one in 925 CE and another three year later, at which important political and ecclesiastical issues were discussed. At these councils, Grgur Ninski fought for the ability to Croatian and the Glagolithic script in the Catholic liturgy. The battles pitted the democratically minded Slavs (Nin) against the rigid autocracy of Latin Split. The Split diocese saw itself as more Latin, than Croat, and wished to maintain close ties with the Holy See in Rome. Ultimately, the opinion held by Split prevailed. On the positive, these councils spurned the construction of many churches in the city, including Sv Trojica (Saint Trinity), Sv Jure (Saint George) and Sv Izider (Saint Isidore), which later was destroyed. A third council was held in 1060 in Split, three years after the separation between Rome and Constantinople. This council reaffirmed the opinions of the previous Split councils - Latin was the only acceptable liturgical language.

In the 10th c. CE, Split began to outgrow the original palatial confines. The city spread west first. Between the 12th c. CE and 13th c. CE, the town's population doubled as the city continued to grow. In the 14th c. CE, the western suburbs were walled to protect them against Turkish invasion.

In 1105, after the death of Petar Svačić, Split, and the rest of Dalmatia, became part of Hungary-Croatia. The city entered into an alliance with Kalman, the Hungarian king; this agreement was known as the Pacta Conventa, which obliged the Croatians to recognize Kalman as king. In the 13th c CE, King Bela IV took refuge in the town during the Mongol invasion. He ultimately went to Trogir, from where the Mongols retreated. Split outgrew the old palace confines and initially spread west, forming a new central square. Though a protectorate of the Hungary, Split enjoyed a great deal of freedom, which allowed it to prosper.

When Louis of Anjou died in 1384, the Hungarian power waned. Seeing an opportunity to add to his Bosnian holdings, King Stjepan Tvrtko I proclaimed himself the king of Dalmatia and Croatia. The citizens of Split were not pleased with his proclamation, but could not fight against it. In 1402, Tvrtko's successor, Hrvoje Vukčić, used unrest in the town to proclaim himself the "herceg" duke of Split. This arrangement caused a great deal of consternation with the local leaders. Observing the strife, Venice came to the aid of the Dalmatian cities. In 1420, Venice took control of these towns and installed a Conte-Capitano to govern.

In the 15th c. CE, Split found itself on the boundary between the Muslim Turks and the Christian Venetians. The Muslim forces would threaten the Christian territories for nearly a century, before retreating to their Ottoman domain. Once the hostilities subsided, trade restarted and Split's prosperity was restored. In 1592, Daniel Rodrigo, a Venetian Jew of Portuguese origin, opened the first scalo (port of call) with a lazaretto (a customs office and quarantine) and the first bank. These facilities made Split a major trading post on the Adriatic Sea.

In the 17th c. CE and 18th c. CE, Split was characterized by lively commerce with the Croatian hinterland and foreign cities. Trade ceased for the twenty-four of the Candian War (1645-1669), in which a declining Venice defended its control of the island of Crete. During this period, the Turkish-Venetian border came dangerously close to Split, running from Jadro through Žrnovica to Stobreč. The closest the Turks came to Spilt was the occupation of Marjan hill, to the west of the city, in 1657. Split's defensive walls were enhanced with star-shaped bastions that are visible today, as well as fortifications added to the eastern end of the port. These improvements were designed by A Magli.

Before and immediately after the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797, Dalmatia was severely depressed economically. This condition was caused mainly by the restrictive nature of Venetian rule. No good could be exported directly to a foreign land, rather it pass through Venice en route. The economic depression caused starvation and disease was rampant. A commission in 1749 found that the population was "decreasing every day with the evident danger that it will disappear completely" (Tanner, 63). The Hapsburgs took control after then Venetians and the situation started to improve. Under the leadership of Napoleon, the French arrived in 1807 to establish Illyria, the first experiment in pan-Slavic unity. The nation lasted six years, before falling to the Austrian forces.

As with most of Croatia, the nationalist movement exploded in the 1850s. In the next decade, there was a struggle for the control of Split. The nationalists wanted to align with Croatia, while the autonomists desired a union with Italy. Ultimately, the nationalists won control of the city council and aligned Split, and Dalmatia, with the Croatians. In the same period of time, the language of instruction in schools switched from Latin to Croatian. In the 1870s, Split prospered, as did much of the world. In 1870, the Gilardi-Betizza became the city's first factory. In 1877, the first railroad entered Split, linking the coastal city with Siverić.

Split, along with Dalmatia and Croatia, joined the Yugoslav federation in 1919. Since the Italians had gained control of the northern port of Rijeka, the Yugoslav government began to develop Split as an alternative port of entry for the interior of the Balkans.

During the period between World Wars I and II, Split developed into a cultural, economic and political center for Dalmatia. Between 1920 and 1927, several improvements were made to the city, including: electrification (1920), a new cemetery at Sustipan (1926), public baths at Bačvice, sports facilities for the Hajduk football club, "Gusar" boating club, meteorological observatory and oceanographic institute, new wing on hospital and the addition of the residential districts of Bačvice, Firule and Mejc. During World War II, the port was bombed by the Germans, who took control of Yugoslavia in 1941. The Allies later bombed the port as they regain control near the end of hostilities.

The region experienced a significant level of growth in the post-war period. New industries developed, which caused an influx of workers from the poorer and more rural areas of the country. These economic migrants are known as the Škver, and many of them came from the Zagora, Dalmatia's interior. Many of these workers found jobs in the city's shipyards.

Split joined Croatia in declaring its independence in 1990 from Yugoslavia. Though it was bombed in 1991 by the Yugoslav navy, the city was almost unscathed during the war of independence. It has experienced an influx of refugees, especially those Croatians that had lived in areas now under the control of Bosnia-Herzegovina or Serbia. Though somewhat depressed economically, the city remains commercially important to the country for its excellent harbor and rail connections to the interior. It is also home to a number of industries, including plastics, chemicals, aluminum and cement. Most of these industries are hidden on the northern side of the peninsula, thus not viewable from the historic center. With the largest airport on the Adriatic coast, it is an important destination for holiday makers, and tourism is an important source of foreign currency.

Airport

The

Split airport is

located about twelve kilometers west of the city. Croatia Airlines

operates a small hub here, mainly linking this tourist center with the northern

(and wealthier) cities in Europe. A few European scheduled and charter

airlines also fly into the airport. Croatia Airlines operates a bus that

transports passengers between the airport and the town. This service costs

HRK 30 and its departure matches with the arrival of flights. It drops

passengers at the bus terminal, which is located at the eastern end of

Riva. If you're staying at a hotel in the Old Town, it is a very

convenient service.

The

Split airport is

located about twelve kilometers west of the city. Croatia Airlines

operates a small hub here, mainly linking this tourist center with the northern

(and wealthier) cities in Europe. A few European scheduled and charter

airlines also fly into the airport. Croatia Airlines operates a bus that

transports passengers between the airport and the town. This service costs

HRK 30 and its departure matches with the arrival of flights. It drops

passengers at the bus terminal, which is located at the eastern end of

Riva. If you're staying at a hotel in the Old Town, it is a very

convenient service.

Accommodations

I

made reservations at the Hotel Bellevue, which is located just to the west of

the Old Town. The hotel was recommended by both the Lonely Planet

and Rough Guide books as budget accommodations. My room was plain,

with one twin and one double bed and a clean bathroom. The facilities were

not the best, but they were comfortable. The most inconvenient part of the

hotel was unlocking the door to the room - I had to jostle the key in the lock

several times to get the door unlocked. On the brighter side, the hotel's

best feature is its location, within walking distance of the city's main

attractions. For almost HRK 400 a night, the hotel was a bargain.

Fax is the best way to contact the Hotel Bellevue: + (021) 362.383

I

made reservations at the Hotel Bellevue, which is located just to the west of

the Old Town. The hotel was recommended by both the Lonely Planet

and Rough Guide books as budget accommodations. My room was plain,

with one twin and one double bed and a clean bathroom. The facilities were

not the best, but they were comfortable. The most inconvenient part of the

hotel was unlocking the door to the room - I had to jostle the key in the lock

several times to get the door unlocked. On the brighter side, the hotel's

best feature is its location, within walking distance of the city's main

attractions. For almost HRK 400 a night, the hotel was a bargain.

Fax is the best way to contact the Hotel Bellevue: + (021) 362.383

Tour of City

I have separated my description of Split into three distinct sections that

follow the city's sights. Click on the link below to proceed to the

appropriate section:

Split Grad

As I mentioned above, my hotel was located just west of the old city

center. I started my tour from the hotel and headed east into the area

known as Grad, or town. The first main street is Marmontova, a

marble-paved pedestrian zone with a number of stores lining each side. On

this particular morning, there was an active fish market occurring in a square a

couple blocks north of Obala Hrvatskog. The vendors were selling

the fresh catch from that morning, including all sorts of fish, octopus and

squid.

|

|

|

| Look at those yummy fish! | The fresh catch is displayed for potential buyers |

I walked east along the Marlje. The street was narrow and strictly a pedestrian zone. It was shaded by four story buildings: the lowest level typically was a store, while the upper three floors appeared to be residences. The street ends at the western edge of the Narodni trg, which has been the city's main square since westward expansion began in the 10th c. CE. It is mentioned as early as 1255 as Platea sancti Laurentii. The square is known locally at the Pjaca, a derivative of the Italian piazza. There are a number of cafés on the square, as well as the Etnografski Muzej Split, which houses the city's cultural and ethnographic collections. It is not worth the HRK 15 admission fee, unless regional costumes interest the visitor. The museum's building is its most interesting feature. Built in the 15th c. CE, it was the town hall during the westward expansion of the city. Its Venetian architecture reflects the Republic's presence here, including the loggia on the first floor and the narrow three windows in the center of the third floor, which are surrounded by pillars and capped with pointed arches.

|

|

|

| The façade of the former Town Hall, now the Etnografski Muzej Split | The entrance ticket to the museum |

Diocletian's Palace

The real reason most people come to Spilt is to visit Diocletian's Palace.

It can be defined as a living museum, as the palace still is home to about 2,000

residents. It has served a number of purposes over the past 1700 years,

and continues to evolve with the city's changing needs.

Diocletian, for whom the palace is named, was born in 245 CE in neighboring Salona. Little is known of his childhood, other than he was the son of a scribe or emancipated slave. He entered military service for the Roman Empire. In 284, after the murder of Emperor Carinus, Diocletian was proclaimed emperor. He did not consolidate his power over the entire empire until the next summer.

Diocletian's reign is best known for his administrative and domestic reforms. First, because the empire was so vast, Diocletian divided the realm into four parts, each administer by a Caesar. Diocletian ruled the eastern front, including the areas of Thrace, Asia and Egypt, while others were responsible for areas in Europe and North Africa. This arrangement allowed each ruler to focus on local issues and strife. Secondly, he separated the functions of government, which allowed for the specialization of work. Though bureaucracy grew, the efficiency of the government improved. He is also known as the emperor that presided over the last great period of Christian persecution. Known for his piety, Diocletian followed the ancient polytheistic Roman religion and viewed the Christian faith as a cult. Instead of reducing the cult's following, the martyrdom of those tortured made the faithful even stronger.

Construction on Diocletian's summer residence commenced in 295 CE near his birthplace. The location was selected because of this proximity and its protected alcove from the Adriatic Sea. Construction lasted ten years and concluded at the same time that the emperor abdicated his throne (305 CE). The palace's architecture has been described as "... a transitional style of an imperial villa, Hellenistic town and Roman camp", reflecting its uses as a home and a garrison for soldiers. It is roughly a rectangular structure, measuring 181 meters on its southern, seaward wall and 215 meters from north to south. The southern half of the palace housed the Emperor and his family and hosted religious and official ceremonies, while the palace's servants and soldiers lived in the northern half. Entrance to the palace was controlled through four gates, each named after a precious metal (and a patron saint later).

After Diocletian's death in 316 CE, the palace hosted a number of Roman dignitaries, including rulers and high officials. The last emperor of the western Roman Empire, Julius Nepot, was killed here in 480 CE by the Germanic Odoacer. The palace fell into a state of disrepair until the former Salona residents took refuge here in 620 AD. They transformed the palace into a protected city by converting the older buildings into homes and businesses. Roman religious temples were converted into churches and new buildings were constructed.

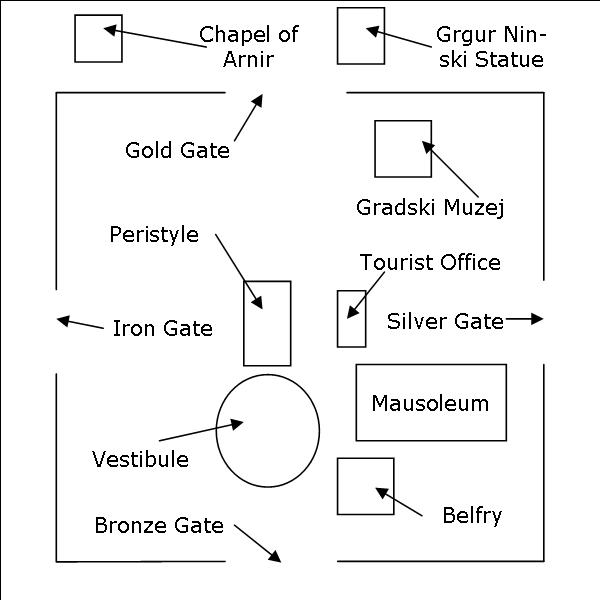

Most of the modern knowledge about the palace is due to the work of three men: Englishman Robert Adam, who diagramed the palace in the 17th c. CE; Frenchman E. Herbrard and Austrian G Niemann, working separately in the 20th c. CE. The palace is a vibrant community today, and was honored with UNESCO's World Heritage Site status in 1979. The diagram below shows the configuration of the palace and the different attractions described on this page.

Iron Gate

The iron gate, known in Latin at the Porta Ferrea and locally as Željeznih

vrata, provided access to the western

reaches of the city. This became an important access/egress point as the

city expanded initially to the western reaches. This gate also is

dedicated to Sv Teodor (Saint Theodore), who is the patron saint of

soldiers.

Peristyle

During the Diocletian period, the Peristyle was the central courtyard of

the royal residence. At the southern end of the courtyard is the Protiron,

which led into the royal residence. The eastern and western edges are

lined with six granite columns on each side. Once the displaced Salonians

moved into the city, the Peristyle became the central market. Now it is

home to some cafés and still serves as a central meeting point for residents

and visitors alike.

|

|

|

| Looking south into the Peristyle. The Protiron is at the far end. | Four of the six granite columns on the western edge of the Peristyle. Notice that they are embedded into the building. |

Vestibule

The Protiron leads into the vestibule, a domed cylindrical room that is

incredibly impressive to view. It was in this room that guests waited for

their audience with Diocletian or his advisors. It is the most

well-preserved portion of the royal residence, with about 80% of the former dome

missing. The room is intimidating, which I am sure is the purpose.

Because it is somewhat hidden, there were not many people in the vestibule.

|

|

|

| The upper portion of the vestibule. The right hand corner shows the opening to daylight. | The entrance from the Protiron. |

Bronze Gate

Known in Latin as the Porta Aenea and locally as the Mjedena vrata,

the bronze gate once provided access to the palace from the sea, which

used to lap against the southern wall. It provided access to the palace's

basements, which lay in ruins until being rediscovered in 1956. The cellar

now houses a number of stalls selling kitschy tourist items. But is

impressive, if only the witness the architectural marval of the arched

ceilings. The gate is dedicated to Sv Julijana (Saint Julia).

|

|

| The arched ceiling of Diocletian's cellars. |

Belfry

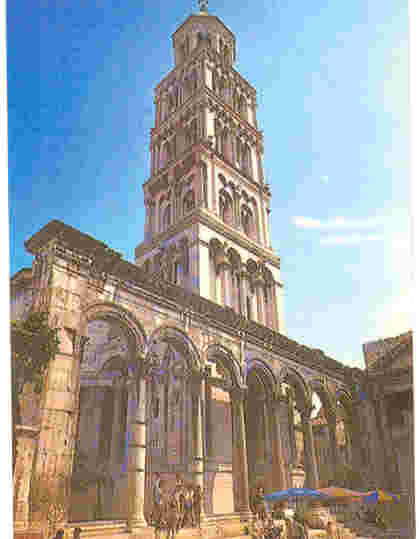

Constructed in the Romanesque style, the Sv Domnius belfry was added to

the chapel between the 12th c. CE and 16th c. CE.

Several great architects participated in the tower's construction, including

Nicholas Florentine and Andrija Aleši. The tower was destroyed in a 19th

c. CE earthquake and completely rebuilt between 1890 and 1906. It costs

HRK 5 to climb the 180 steps to the top of the bell tower. The climb can

be somewhat harrowing experience, as the steps are rather steep. From the

upper balcony, I got a great view of the palace and surrounding area. On

the southern wall near the tower's entrance is a 15th c CE Egyptian black

granite sphinx brought to Split during the tower's

construction.

|

|

|

| The 60-meter tall Sv Domnius bell tower | Admission ticket to climb the bell tower |

| The view from the belfry is amazing. Split's Old Town and surrounding area can be seen from the upper balcony. | |

|

|

|

| Looking west toward Marjan hill | Looking northwest toward the industrial area of Split |

|

|

|

| Looking north over the Old Town | Looking northeast |

Mausoleum

Built as part of the original structure, the mausoleum housed the bodies of

Diocletian and his wife Prisca after their deaths; their bodies rested here for

almost 170 years, before they mysteriously disappeared. In 653, the

mausoleum was converted into the Katedrala svetog Dujma, honoring the

martyred bishop of nearby Salona and patron saint of Spilt. The

mausoleum's octagonal shape has been maintained, which a Romanesque choir added

behind the main altar. Twenty-four columns support the domed roof; each

column has an ornate capital on its top. The church is a treasury of 13th

c. CE through 15th c. CE artwork, including the 15th c. CE

stone altar by Juraj Dalmatinac. The north altar is dedicated to the

co-protector of the city, Sv Anastasius, a tanner from Aquileia who was thrown

into the Jadro River in Salona with a mill-stone around his neck. Two of

the chapels were being restored during my visit. Unfortunately,

photography was not allowed in the church, a rule that was enforced

strictly.

Silver gate

Known in Latin as the Porta Argentea and locally as the Srebrnih vrata,

this entrance is dedicated to Sv Apolinar (Saint Apollinaire). This gate

provided access to the eastern suburbs, which developed later than their western

counterparts. The area just outside the gate now houses a daily market

selling many shoes.

|

|

| The silver gate, as seen from the belfry |

Tourist Office

The city's tourist office is housed in a small Renaissance church dedicated to

Saint Roch. The bureau maintains a website,

which is somewhat incomplete in English.

|

|

| The Renaissance church dedicated to Saint Roch; it now serves as the city's tourist office. |

Muzej Grada

Splita

The city's historical museum is housed in the former Papalić Palace.

Considered one of the city's finest examples of late Gothic architecture, the

palace was built by Juraj Dalmatinac for one of the city's most influential

noblemen, Dmine Papalić. The museum's history can be traced to this

owner who, with poet Marko Marulić, collected a number of stone fragments

in the 16th c. CE from the ruins at Salona. These relics were displayed in

Paplić's courtyard.

In 1911, the municipal library was founded; part of its charter stated that the town's museum must be attached to the library. The museum occupied two rooms in the Bernardy Palace in 1925 and expanded to six rooms in 1946. By the end of July, 1946, the term Muzej Grada Splita was attached to the collection. In 1950, the Papilić Palace was acquired to house an exhibition celebrating the 500th anniversary of Marko Marulić. Two years later, the palace was opened as the new home of the museum. In September 1983, renovated areas of the palace were opened to show the museum's entire collection.

The museum provides an excellent introduction to the history of Split. It chronicles the history of the town, from its foundation as Diocletian's palace through the recent war of independence. The collection is labeled in Croatian only, but the storyboards are written in English, as well as a couple of other languages. I highly recommend paying the HRK 15 entrance fee, especially to see the banquet room on the second floor. Notice the ornately painted ceiling.

|

|

|

| The ornately painted ceiling of the second floor banquet room | Entrance ticket to the museum |

Gold Gate

Known in Latin as the Porta Aurea and locally as the Zlatna vrata, this gate is

dedicated to Sv Martina (Saint Martin), another patron saint of soldiers.

Linking the palace with Salona and the outside world, this gate was the palace's

most important entrance. Its grandeur has been masked temporarily, as a

full-scale restoration appears to be occurring

|

|

| The gold gate, which was the main entrance to the palace |

Grgur

Ninski Statue

Grgur, the bishop of inland town of Nin, fought for the ability of his Catholic

Croat colleagues to use the vernacular Slavic for liturgical purposes.

Unfortunately, he lost this battle twice to his Roman-loving counterparts on the

Dalmatian coast. Because of his steadfast resolve to the early Croat

movement, he is honored with a statue outside the gold gate entrance. The

work was completed in 1929 by Meštrović to commemorate the millennium of

the first synod of Split, when the aforementioned issue was discussed. It

had been installed in the center of the Peristyle, but was moved here during

World War II when the Italians were cleansing the city of nationalistic symbols.

|

|

| The statue of Grgur Ninski by Meštrović |

Chapel of Arnir

The Crkva Sv Eufemije was one of the first churches built outside the palace's

walls. It is first mentioned in 1069 as part of a Benedictine convent, and

was destroyed by fire in 1877. The foundation of this three-nave church

still can be seeing just northwest of the gold gate. A small chapel,

dedicated to Sv Arnira, remains. It was constructed in 1445 by Juraj

Dalmatinac. Behind a glass shield is an altar and sarcophagus carved by

the builder.

Marjan Peninsula and Riva

To the west of Split's old town is the Marjan peninsula. The

Marjan hill is first mentioned in medieval documents by the names Mons

Serranda, meaning prohibited for pasture and felling of trees, and Mons

Kyrieleison, because of the number of churches in the area. The name

Marjan probably originates from a Roman nobleman who owned the land. On

maps, it has been referred as Marnano, Mariniano and Murnano.

From the 15th c. CE, the hill hosted a number of hermit caves that were occupied by priests looking for solitude and enlightenment. A number of these caves have been converted into small churches, which are the destination for pilgrimages by the local residents. One of the churches is built into the side of the hill.

I hiked up the hill, which is a pleasant afternoon or early evening walk. At 123 meters above sea level, the top of Marjan hill is home to Državni Hidrometeorološki Zavod (a meteorological station), Opservatorij Split-Marjan (celestial observatory), a monument to Luka Boti and a small zoo. I headed further west along the path, and encountered some of the aforementioned cave churches. Two notes of interest: 1) there were a couple of mountain climbers repelling one the hill's rock faces, and 2) I almost stepped on a snake while it sunbathed on the rocky footpath.

|

|

|

| St Hieronymous's Chapel, which is built into the side of Marjan hill | A mountain climber repelling the side of the hill |

|

|

|

| Split's harbor, as seen from Marjan hill | Beautiful flowers on the path |

The path ends at the western tip of the peninsula. I followed the main paved road into Split, which led to Riva, the city's pedestrianized waterfront area. The street received its current appearance in the 19th c CE during the brief French occupation; it was extended and graveled. It is now lined with cafés on the north side and trees and benches on the south. It is a pleasant place to have dinner, an evening cocktail or simply people watch.

|

|

|

| The cafés on Riva await you ... | Where the Riva meets the water |

Eating Out

Unfortunately,

Split's restaurant offering is minimal, with the exception of the cafés along

Riva. I ate lunch one afternoon at restaurant associated with the Hotel

Adriana. I started with the krastavac salat, which was

cucumbers soaked in vinegar. The main course was pljeskavica, which

resembled Salisbury steak. It was a pleasant dining experience, and I

would recommend it. The town's best eating establishment is probably the Restaurant

Sarajevo, located just off the Narodni trg. It specializes in

local dishes, including meat and fish. Similar to my experience in Zagreb,

I found the fish prices to be quite high. The waiter, however, did find a

smaller fish for me, which reduced my bill considerably. I would recommend

this restaurant, as well.

Return

to Main Croatia Page